The final chapter of 3 day Koji camp with Nakaji in Takashima (Vol.3)

The Koji lover’s dream, Koji camp with Nakaji has finally come to its end. Today we are going to learn how to judge when Koji is ready, and how to handle the preservation. The lecture includes interesting facts on Sake and resident flora that influence our health in body and mind.

First topic: How can we know when Koji is ready? What to do in the last 12 hours?

So for the past two days of this Koji camp, we have been learning how to prepare rice (soak, drain and steam), how to inoculate the seed Koji and the temperature and humidity control in timeline. See previous post for the earlier process of Koji making below.

Related articles;

Koji lover’s dream, 3 days Koji camp with Nakaji in a special setting in Takashima, Shiga. (vol.1)

The second day of Koji camp with Nakaji in Shiga. A jam packed day learning from the professional temperature control to the rule of fermentation (Vol.2)

The first thing we are going to learn today is about “DEKOJI”, literally means getting the Koji out (of incubator).

The Koji rice has been kept warm in a canvas and blanket for the last 40-some hours, and also has been producing heat by itself.

In fact there is an important tip that Nakaji, the initiator of this Koji camp needs to tell you. The temperature zone (of Koji rice itself) that you chose to maintain in the last 12 hours before getting Koji out of the tray, will have a big impact on the type of enzyme that it produces.

If Koji is kept above 40 degrees for the 12 hours, Koji would produces a lot of enzyme to provide light and sweet flavour. In contrast, below 40 degrees contributes to the production of enzyme that produces rich and strong Umami flavour.

For Sake making purpose, Koji is often kept at around 42 degrees, which ensures the environment for more than 100 types of degradative enzyme to deliver light and fresh flavour.

For the timing to finish Koji making, it is ideal to have the stable temperature of 38 degrees for the last 12 hours. That would approximately be 48 hours mark from the point you started making Koji. After 8 hours from “DEKOJI”, Koji starts producing spores. This is not needed for Sake making as spores make the taste rough and also colours Sake.

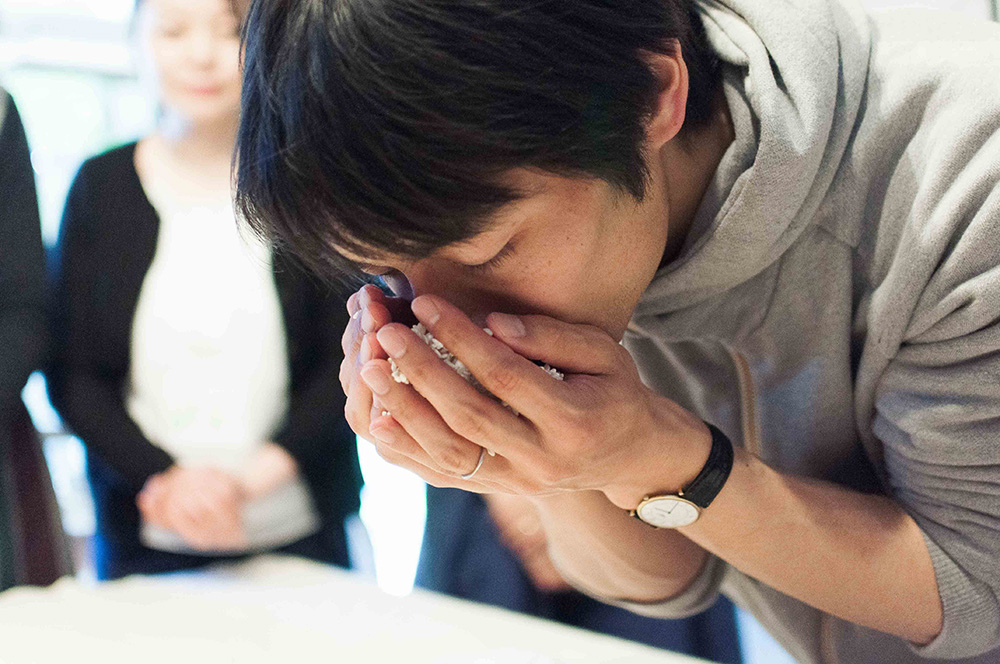

It’s also important to touch, sniff and sample taste some Koji grains. Good Koji should smell like roasted chestnuts, and soft and fluffy when you scoop them up with your hands.

Nakaji checking the result of Koji by sniffing

The best season to make Koji

As far as the Japanese climate concerns, the best season to make Koji is around June, July and August when the humidity level is highest with high temperature. Mold (not necessarily Aspergillus Oryzae) loves the warm and humid environment. So Nakaji says that you could even leave the Koji out in a balcony without an extra heat source to cultivate it.

The advantage in Autumn and Winter is easier temperature control (as it could get extremely hot in Japan in the mid-Summer), but you may have to pay extra attention on the humidity.

In the coldest time of the year, you may want to inoculate seed Koji at 36 to 38 degrees instead of generally advised 34 degrees as the temperature drops dramatically while you are making steamed rice.

All year around, the ideal humidity (of the rice) is 90%. The wooden box or tray is most suitable to keep the best humidity environment and also to sustain the stable temperature.

After Koji is ready, you still have to naturally dehydrate Koji

So now Koji is ready! Nakaji advices us to spread it on a canvas cloth in order to release heat. You could even use a electric fan in mid- summer.

What’s special about his method is that he draw a spiral line on the Koji rice to include the surface for the air contact. It is logical and beautiful. After this process of “dehydrating”, you can store Koji for up to one month in a fridge, or 3 months in a freezer.

Most of the commercially available Koji must be dehydrated (otherwise Koji keeps on fermenting) as well, but be careful with dry Koji you buy at a store. It may have been treated in hot air that oxidizes Koji, and the amount of living enzyme maybe 10 % less. For this reason Nakaji recommends to use an extra amount when using dry Koji to make fermented food.

One more useful tip he gave: try to cool down Koji completely particularly when you plan to use it for lacto-fermented food. The fermentation would jump-start if you use Koji straight out from the incubator.

“Hana-michi”, the spiral line to release heat from Koji

Short break: today’s fermented food lunch plate

So now we get much-awaited fermentation lunch plate that’s prepared by Masako Taya (the owner of the venue, The house of Herb) and her fellow chefs.

Menu: Japanese paella with firefly squid marinated in Hishio (left over from the previous night) and vegetables, tofu made of Kuzu and soymilk, dressed with Dashi sauce. Acqua pazza made with seafood marinated in Amazake. Chopped salad with Allernon. Allernon is a rice powder based yogurt using lactic acid bacteria taken from Funa-sushi, a local speciality in Shiga.

Fully charged with fermented lunch. Now Nakaji reveals facts on Sake

Nakaji is a former member of Terada Honke natural Sake brewery in Chiba. He shared some interesting facts about Sake making with us. Sake in general is diluted with water to lower ABV (alcohol by volume). Without this step, ABV stays above 20% and and is too strong for us to drink and at the same time enojy it.

There is also “Genshu”, non-filtered raw unprocessed Sake that has ABV of 18-19% available in market but even that is sometimes diluted 1% for the same reason.

Why lowering ABV? Sake has always been made for people to enjoy its Umami and Amami (sweetness) flavour in tradition. The high ABV makes your tongues numb, not being able to feel those flavours. The best level is 15%, which was discovered in Edo period when restaurants diluted Sake by themselves before serving to the guests. After much feedbacks, Sake makers took up this process before distributing it.

Talking about traditional Sake, there is also this thing called “Doburoku”. It is raw cloudy non-filtered Sake, which sounds a lot like Genshu described above but the making method is different. For Genshu, the ferment is only roughly strained but for Doburoku it’s not strained at all.

Both are made from the same ingredients (steamed rice, water and Koji) but they are all mixed at one go for Doburoku, whereas the steps are applied three times for Genshu (or Sake). The latter method is used to naturally bring ABV higher. This is why Doburoku has only 14- 15% of ABV which is about the same as wines.

Resident bacteria from your mother keeps your guts healthy

“Making Koji means that you are supplying yourself beneficial bacteria.” says Nakaji. Here’s what he means;

When food with unfamiliar bacteria comes into our intestines, our immune systems wouldn’t accept them. It’s important to increase them by yourself, and that needs a lot of home-fermentation.

Take our hands for instance. They are full of resident bacteria. So when you eat fermented food such as Nuka-duke (vegetables pickled in rice bran bed) that your mother made, your guts would recognize the bacteria and accept it smoothly.

Interesting that we supply this mostly from our mother. Of course father contributes by skin contact, but mother takes much more important role from the beginning. A baby is born, they are protected with lactic acid bacteria that has been in their mother’s wombs. (So if you lick a new born baby they taste sour.)

Nakaji says it is better not to rinse babies when they are born. They are also able to break down oligosaccharide and lactose when they a re breast-fed.

“Eating your mother’s handmade fermented food makes your intestine healthy that also increases serotonin.” says Nakaji.

Nakaji talks about happy hormone “serotoin”

There are roughly two types of chemicals that relates to happy state of mind. One is called dopamine and the other is serotonin.

The dopamine type of hormone creates “brain-based happiness”. This is a type of happiness that can be gained by striving to achieve something. There has to be a goal and a lot of effort is spent, that naturally involves stress.

The serotonin type of hormone creates “guts-based happiness”. This gives you to stay in good mood without having to try achieving something. It’s a kind of mood that “I’m just so happy all the time though I don’t know why.” Nakaji says eating fermented food that’s rich in lacto bacilli triggers the production of serotonin, and makes you feel good every day without anything special to do. Hmm. I’m thinking of someone who gets grumpy when he is hungry… 😉

The group shot in Masako’s garden. Everyone is holding freshly made Koji in the camp.

So how did you like this series of article?

Nakaji still travels around the country to spread fermentation life in Japan. The next camp would be in September at Yoshimi Kobayashi’s kitchen “Okan no Koji” in Sakai city, Osaka. In October he organizes another school that’s meant for non-Japanese people. Don’t miss it.

Coming events:

16-18 September Nakaji’s Koji school in Sakai, Osaka at Okan-no-Koji (http://www.okannokouji.com/) 6-8 October Nakaji’s Koji school special edition for non-Japanese enthusiasts

Related articles;

Koji lover’s dream, 3 days Koji camp with Nakaji in a special setting in Takashima, Shiga. (vol.1)

The second day of Koji camp with Nakaji in Shiga. A jam packed day learning from the professional temperature control to the rule of fermentation (Vol.2)

Teacher

Nakaji

・Blog

・Official site

Supporter

Masako Taya

・Official site

・「Takashima Hacco Tsunagari-tai」

Links

・http://hakkou-takashima.com/

・http://takashima-marugoto.jp/

Teacher

Nakaji

・Blog

・Official site

Supporter

Masako Taya

・Official site

・「Takashima Hacco Tsunagari-tai」

Links

・http://hakkou-takashima.com/

・http://takashima-marugoto.jp/

・http://www.allernon.jp/