A tour in Sake brewery│Sawada Shuzo strictly sticks to the traditional brewing method

Hakuro is Sake made with a huge respect to the traditional manufacturing method at Sawada Shuzo (Sake brewery) in Chita peninsula, Aichi. The brewery was established in 1848 and has a very interesting history and a commitment to the traditional manufacturing method. Hidetoshi Sawada, Kurabito and executive vice-president introduced their story to us.

Hakuro, Sawada Shuzo strictly sticks to the traditional brewing method for 170 years.

https://haccola.jp/en/2017_03_27_1008/

Finally, we are entering their Kura (a brew house)

After the crash course that totally made me immersed into their story, Hidetoshi gave us a tour in their Kura, a brew house.

Sawada Shuzo recovered from the two earthquakes.

Sawada Shuzo was established in 1848, and fell over once in 1854 at the time of Tōnankai earthquakes. This was also mentioned in the old diary book they found at the brewery. It’s written that “a big wave swept our barrels.” and such.

After the earthquake, they relocated to the current location: Tokoname city, but there was a big earthquake again in 1944 during the World War II and they had to restore the brewery one more time.

Their ancestors laid down their own pipes to get pure spring water still in use.

First Hidetoshi showed us their well water outside. Their ancestors laid a private pipe from 2km away, the hilly area in Chita peninsula to get this pure spring water, which is still in use today. Surprising is that this water pipe runs since the Edo period!

It’s soft water with a low mineral content (hardness 20), which means that there is very little for enzyme to live on. Making Sake is easier with high mineral content. With this water, it’s hard to keep the stable quality so Sawada uses blended water of this soft water and hard water (hardness 120) from the sea to make Shubo, the mother culture.

It was lucky that their ancestors were able to find this spring water.

Chita peninsula does have some access to spring water which have been used for many Sake breweries since long ago, but it wasn’t enough for industrial and agricultural use. Aichi Prefecture specially started supplying water for industrial use in 1961.

Sawada could have gotten water from the ground, but due to its location they only have access to the sea water mixed with hard and clayish soil that has a high iron content. This would cause the coloration and cannot be used for Sake making. It was lucky for Sawada’s ancestor to find this spring water from 2km away, so they could use it for Hakuro.

The traditional steamer “Koshiki”

Inside of their Kura, there was a huge wooden steaming vat standing. This is called “Koshiki” in Japanese. They used to steam 1 ton and 200 kilos of rice at once until the bottom of this steamer fell out in 2016. 9 out of 10 fermentation experts around Hidetoshi advised not to use it anymore, but Hidetoshi couldn’t give up on this precious traditional steamer.

At that time, there was still one man in Osaka who could make this huge Koshiki. With much hope Hidetoshi asked him to make a new one before his retirement in 2020.

This long straw rope is only made in Kaga, Ishikawa prefecture.

The straw that’s roped around Koshiki also has a style, and the one you see in the photo below is Tanba, Hyogo style. This style is not only beautiful but also retains heat and makes it easy to transport Koshiki.

This long straw rope is only made in Kaga, Ishikawa prefecture where they need it for Yukizuri (ropes to hang the lowest branches from the top of the tree in winter to protect them from snow.)

Currently Sawada orders from there, but Hidetoshi is not sure how long that could last. The straw rope made in China had a certain aroma and less durability so it could not be used.

The most important part in Sake making is steaming rice

The most important part in Sake making is steaming rice. If the rice gets overcooked or squeezed to become Mochi, that part cannot become Koji. In this Koshiki, there is a room for two persons to work inside, but Sawada restricts it to one person so there would be only two feet that squash the rice. Moreover, the person who scoops up the rice should definitely not reposition his feet. More move, more waste. Alternatively, they could have dug the rice all the way down to the bottom and let one person stand there, but he would most probably be steamed like rice too.

No matter they are steaming 100 kilos or 900 kilos (their current maximum), the end time of steaming does not change. It’s a race against time and very heavy physical work. Imagine yourself alone with 900 kilos of steaming rice in a barrel…

I asked Hidetoshi if they fill Koshiki with such a lot of rice all at once. He said “When we steam 900 kilos, we usually divide it to three layers. That depends on the types and the usage of the rice. When preparing for big Sake production, we’d do it at one-go. Everything is done by hands, even if it’s 900 kilos.”

By now my mind is totally brown away with an amount of man power work behind Hakuro’s production.

Next serious step: soaking the rice

There are three big tanks for soaking rice. Sometimes the soaking time needs to be measured very punctually by a stop watch, which they use 15 small barrels to take care of. The extreme care is required for this process: quickly filling Koshiki and make three layers, placing the rice with or without mixing air depending on the purpose of rice afterwards.

130-year-old raw wood for Koshiki

Next, he showed us 130-year-old raw wood from Okumikawa. This is a very valuable piece as it is extremely hard to find today. For building materials, reddish and soft cedar tree is valued, but for Sake making, hard wood that’s durable for water and heat is required.

A good craftsman should have a strong network to get information on where this hard wood can be found.

Even if the tree is found, the part that can be used is limited: the centre and the part with growing rings. Koshiki made of this part can retain the heat inside (but not hot on outside), and the excess water can be absorbed by the wood so the steamed rice does not get too sticky.

A piece of wood that’s used on the side of Koshiki. Screws are also made of wood.

Sawada’s Sake-brewing rice

Rice that’s suitable for Sake making should have a very little protein and is easy to melt.

When we make Koji, important is let the mycelium penetrate into “Shinpaku”, the white core of rice. This way the rice is melt easily and good Sake is made.

However, Chita area rather has a warm climate so the rice grown here would have a lot of protein and requires extra effort to produce a good Sake-brewing rice.

Sawada Kenichi re-evaluated Chita’s local rice with the future in mind.

Yamada Nishiki, a high-quality Sake-brewing rice is made in Kato-city (old Tojo town), the middle of Hyogo prefecture that has the best climate for the growth of the Sake rice (very cold in the night and warm in the day time) and the best suitable soil condition.

“There is this tall rice called Omachi that’s mainly grown in Okayama, but again this does not grow in windy Chita. In such circumstance, however, Kenichi Sawada, the current representative director and chairman concerned the future and re-evaluated Chita’s local rice some years ago. Thanks to that, we could also start growing Aichi’s Sake-brewing rice Wakamizu in our own rice field since 2002.”

Aichi has a special rule that up to three types of Sake-brewing rice can be produced.

Aichi has a special rule that up to three types of Sake-brewing rice can be produced. Currently they are Yumesansui, Wakamizu and Yumeginga. At first only Wakamizu grew in this area, but in 2010 Aichi prefecture developed Ginjo-Sake rice that could be grown in this flat region. Even if they tried to grow Yamadanishiki in Chita, it wouldn’t be easy to achieve a good quality. What’s more, it is not allowed for the name to appear on a label.

Koji tray to make all Koji for Sake making at Sawada Shuzo

Sawada family makes all Koji for Sake making on wooden trays (“Koji-buta” in Japanese). And I mean ALL of it. If you’ve made Koji yourself before, you may be able to imagine how much work that would be. Instead of making Koji in one huge bundle, they choose to look after them on every single tray. All the steamed rice is transferred to each tray, brought to Koji incubation room, and mixed by hands under a delicate temperature control.

A real good Koji-buta (Koji tray) is like an artifact.

I asked what they do with old Koji-buta. Hidetoshi said that they disassemble and repair them. A real good Koji-buta is like an artifact, he says. It has to be light and durable enough when they drop it to let the air out from Koji rice.

The higher the quality, the more valuable it is. This is why Sawada keeps recycling the old trays with utmost care.

The trays you see in the below photo is only a small part of all trays they have.

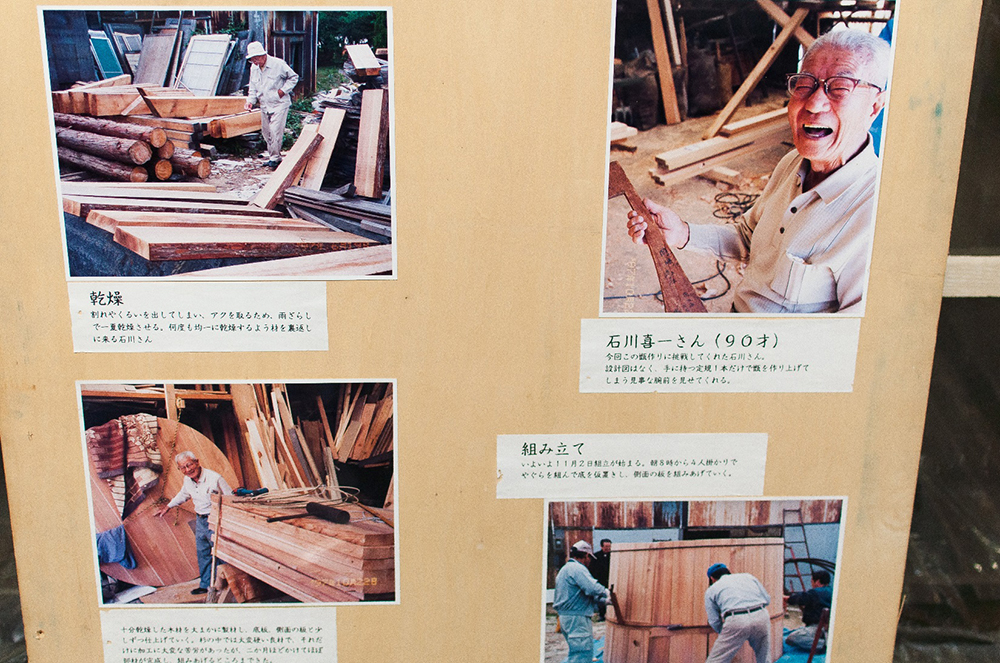

The true artisan Kiichi Ishikawa and Hakuro’s Koshiki

To make good Koji, you need a wooden vat Koshiki. The problem is that there is much less demand on it than before because of its challenging manufacturing process and the migration to an automatic rice cooker. There are only several professional who can make this in the whole country.

Kiichi Ishikawa was one of them.

This Koshiki became a master piece, and his last work at Sawada.

He was 90 when Sawada family asked him to make a huge Koshiki some years ago. The family trusted him completely as he had been making excellent wooden tools for them for decades.

Kiichi was a true artisan, who followed his gut feeling rather than an instruction manual or a design drawing. Everything was made with his intuition – the choice of raw materials, sawing lumber and drying before assembling. This Koshiki became a master piece, and his last work at Sawada.

Silent resident in Kura, Sake yeast

Hidetoshi shared his secret ambition of cultivating the yeast impregnated in their Kura in the future. He thinks that the inhibiting yeast most probably derives from Association Yeast No. 7/Kyokai Kobo No. 7 that they used to use before. This yeast produces high levels of banana-like isoamyl acetate.

The current trend in the industry on a side note is the fruity, appley ethyl caproate, which Kyokai Kobo No.9 and 18 have.

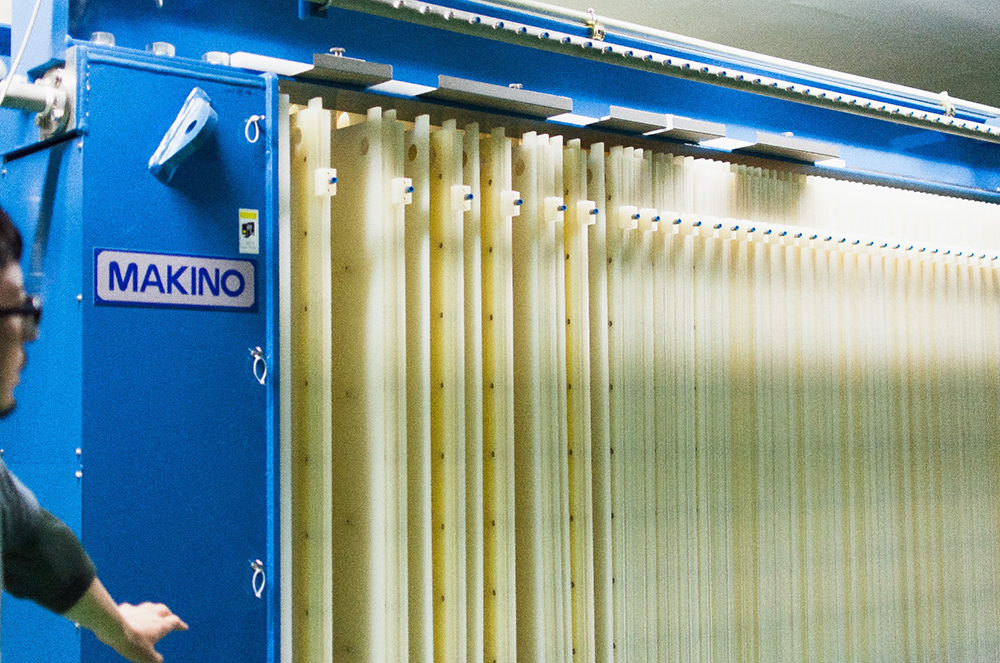

A filter press is also Tokoname brand

By now you must have learned that Sawada’s Sake is made with the huge effort and unmeasurable amount of manual labor. What do they do for filtering then? Thank god, they utilize the advanced technology – not to save their energy, but for the very practical and solid reasons.

Their secret (?) weapon is this Makino filter press from Makino Co., Ltd. in Tokoname city, shown in the photo below.

After pressing, liquid (Sake) is extracted and only Sake lees remains in the machine.

Previously Sawada used a different filter press from another company, but they switched to this Makino design because it was handier, more efficient, and for the fact that it made it possible to filter their Sake hygienically. Of course, this cultivated the mutual cooperation in local society too.

Though it’s not shown in the photo, Moromi (fermentation mash) is first pumped into the machine by a hose pipe, then press-filtered in the accordion-like part. After pressing is done, liquid (Sake) is extracted and only Sake lees remains in the machine.

Originally Makino Co., Ltd. was specialized in extracting soil that is essential to Tokoname pottery. While meeting the demand from the industry to extract a good solid part of mud, they realized that they could apply the same concept for extracting the Sake from Moromi mixture.

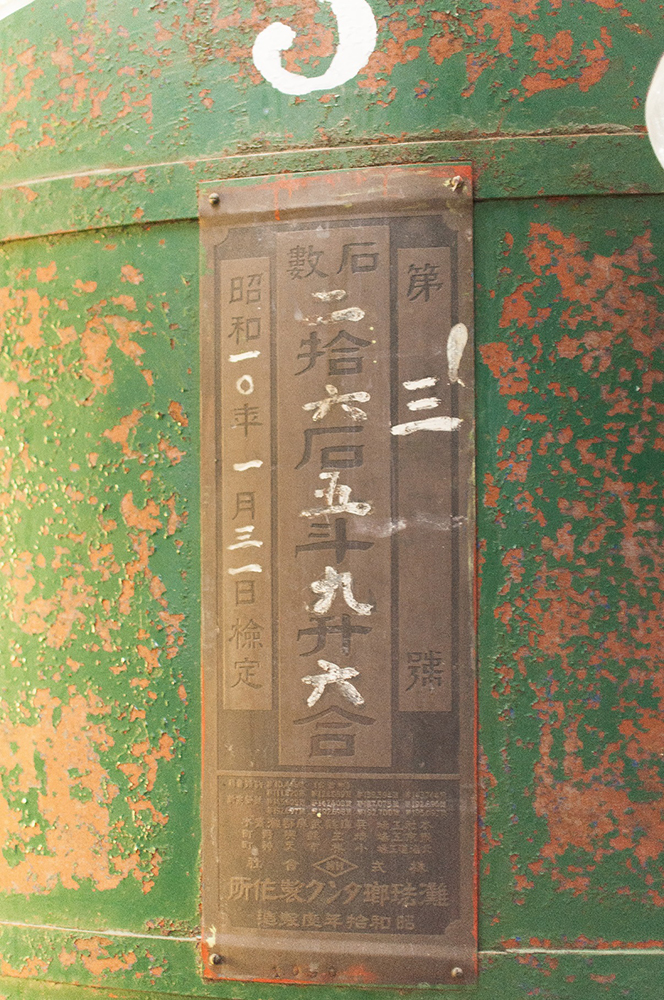

The enamel tank made in 1930s

While most of the Sake breweries in Japan started using enamel tanks after the war, Sawada pioneered Sokujo-method and took the enamel tanks in way before the others did.

On the tank it was written that the tank can contain around 4800 liters. Currently it is not used to store Sake, but to store water or distilled alcohol.

Hakuro-Bai, Edo-style Umeshu plum wine from locally produced Ume

Hakuro-Bai

At the end, Kaoru Sawada, the head of Sawada Shuzo explained this special Umeshu they make at Hakuro.

Umeshu is a plum wine made from Ume plum, sugar and Sake. To make this, Sawada uses a hybrid Ume called “Souri-Ume” that is bred from Ume tree and peach tree. This breed has been developed by local farmers in Chita city in the last 100 years. Souri-Ume is smaller compared to Nanko-Ume, but it does have a good acidity and suitable for Umeboshi or Umeshu making. The plant itself is also quite resistant to disease and pest, so overall, it’s an easy one to grow and harvest.

Straw ash removes the bitterness and maximize the Umami flavour.

Again, Sawada sticks to the traditional making here. Their recipe comes from the old food encyclopedia called “Honcho Shokkan” from Edo, published in 1695. This book covers everything about food and its benefits, and describes the recipe of Umeshu, using aged Sake and straw ash.

Sawada adopts this method and makes the ash from their rice Wakamizu. The trick is to burn it little by little, or everything gets burned out white and the beneficial effect is gone. Next, they dissolve this ash in water and soak the freshly harvested Souri-Ume overnight. This will remove the bitterness and maximize the Umami flavour. How smart that people from Edo knew that alkaline property from ash could be used this way.

With a big help of volunteers, hulls from all Ume are removed by hands. Finally, the Ume will be layered with sugar crystals (made from sugar beet in Hokkaido, crystalized in a special room for 3 to 4 weeks), and Junmai-Ginjo-Shu will be poured all over. After three months of maturing, Hakuro-Bai is ready to consume.

Sawada pays a huge respect to this ancient wisdom to make their Hakuro-bai.

In most of the cases, highly distilled liquor with an alcohol content of 35% is used for making Umeshu. However, Junmai-Ginjo that’s used at Sawada has an alcohol content of around 16-18% that is standard for Genshu (raw Sake).

When using lower alcohol content like this, normally you would have to rely on osmotic pressure by sugar to extract essence from Ume. This is where the straw ash works magic on. Soaking Ume in the ash-water makes it easy to extract the essence, even with half quantity of sugar is used. Sawada pays a huge respect to this ancient wisdom to make their Hakuro-bai.

Sawada Shuzo is a brewery of tradition and innovation

Through this intensive visit, I enriched my understanding of Hakuro as Jizake that maximize the joy of their local cuisine made with strong flavour of red Miso or Tamari.

Sawada Shuzo is a Sake brewery that has always been stepping across a line and at the same time earnestly keeping their traditional manufacturing method. A very interesting brewery with a path-breaking history.

Please discover what is fermenting there.

How did you like the story?

This was only a small part of everything that’s hot in Chita. I encourage all of you to go discover everything else that’s fermenting there.

Sawada Shuzo

Sawada Shuzo official site

Sawada Shuzo online shop

Hakuro, Sawada Shuzo

Hakuro-Bai, Sawada Shuzo

Related Links

Makino Co., Ltd. official site

Hakuro, Sawada Shuzo strictly sticks to the traditional brewing method for 170 years.

https://haccola.jp/en/2017_03_27_1008/