Koji, You Are Already Eating It.

Think of a few Japanese foods and what comes to mind? Surely in that list most or all involved a special rice mold called koji. Sake, mirin, miso, soy sauce and rice vinegar all crucially relay on it. While koji is common throughout many foods in Asia, in Japan it is called ‘kokkin’ or national bacteria.

First of all a distinction should be made between koji and koji-kin. Koji is the end result of a grain, usually rice but it could also be barley, rye or buckwheat, which has been steamed, covered with koji-kin and left to act as a host for the spores. Koji-kin, whose scientific name is Aspergillus Oryzae, is a mold spore, actually a fungus.

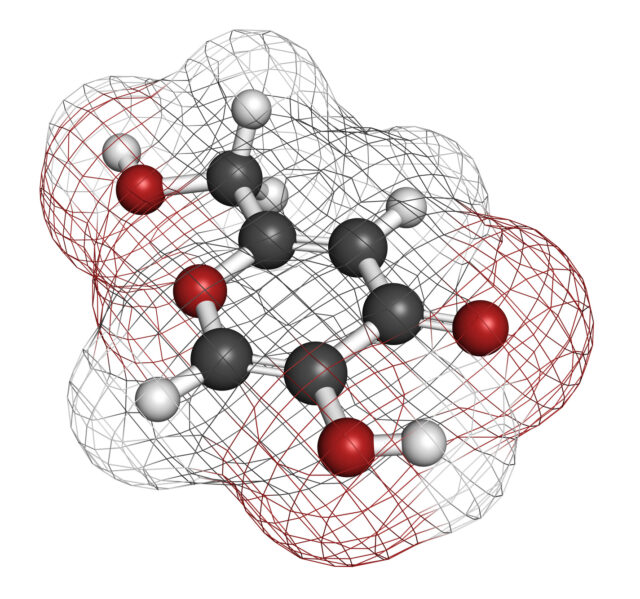

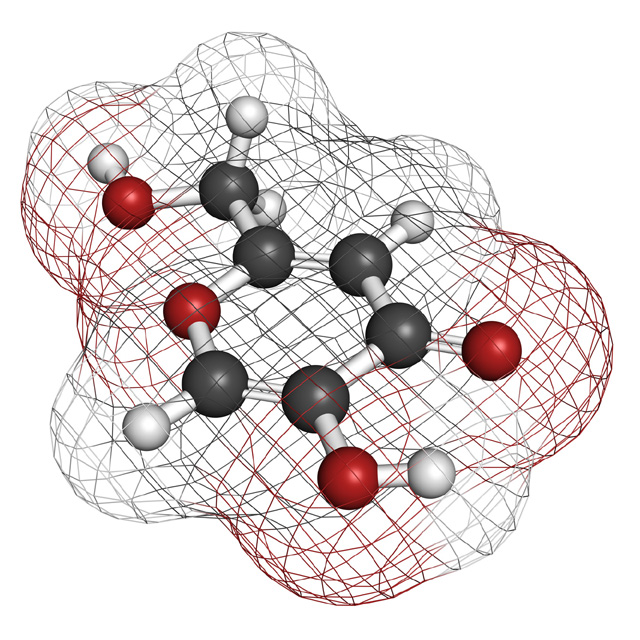

On a microscopic level growing koji is quite a beautiful looking thing. Once the koji-kin has absorbed the nutrients of the rice, delicate long filaments called hyphae grow out tipped with reproductive spores, these are spread out in search of new hosts. This process of the fungus propagating on the rice produces enzymes which break down fats, protiens and starches into amino-acids, glucose and peptides that feed yeasts and bacteria. Ash, rich in phospahtes, potassium and magnesium, is also often mixed in to foster spore production. The whole process takes around four days before the steamed, moldy rice is ready to go on to produce an array of fermented foods.

Koji in Sake Production

Both sake and mirin are made in a very similar process, have koji-rice mixed with regular rice and then a yeast to accelerate the fermenting process. Mirin has become quite a familiar cooking ingredient throughout the world. It is a slightly sweet and very rounded flavour. The alcohol content of mirin can range from fifteen to on percent, with most commercially consumed mirin been at the lower end of the scale.

Of all the ingredients that koji features in the most complex and painstaking process is involved in sake production. There are fundamentally three types of koji-kin; yellow, black and white. Standard Japanese sake, which should be referred to by it’s true name nihonshu, is made with yellow koji. It is far more sensitive to temperature changes than black or white koji. For this reason it is almost exclusively brewed from the central to northern regions.

Shochu, which is distilled rather than brewed originated and is still most commonly found in the south-western regions of Japan, especially Kyushu, uses a heartier white koji-kin that stands up to the warmer more humid climate. It has a shorter history than nihonshu, starting from the sixteenth century.

Awamori, native and pretty much exclusive to Okinawa uses black koji. Shochu can also be made using black koji, but as it tends to stain easily fell out of favour until a non-staining black koji was developed in the 1980’s.

Whereas beer begins with starches that are broken down into sugars through a malting process, sake doesn’t, this is where koji comes in. It provides the natural enzymes to create the sugars, some of which produce alcohol through fermentation, others do not ferment at all but affect the sweetness and texture of the sake.

The heart and soul of every sake brewery is the koji room or koji moro where the koji is cultivated as the first stage in the brewing process known as seigiku. Recently there has been a rise in the use of koji moking machinery. But still all of the top-of-the-line sake will still have the koji cultivated by hand, under the watchful eye of the most experienced and highly regarded craftsmen at the brewery.

Koji in Koji in Miso Production Production

In miso, soy beans are fermented with koji in a tightly packed airtight environment.

Through this natural fermentation process cooked beans have there proteins, oils and fats converted to amino acids, simple sugars and fatty acids which are easily digested, along with probiotic microflora. However, one would do well to seek out unpasteurized varieties where health is concerns, as many of the beneficial elements are lost during pasteurization. Everyone familiar with an older relative in Japan is well aware that miso should never reach a boiling point when preparing soups (miso shiro) or other sauces, as not only the complexity of taste but also many of the probiotic benefits are compromised. Containing calcium, iron, folate, tryptophan, protein and the hard to come by vitamin K. It is widely believed that the sodium in miso has far less adverse affects on people with high blood pressure due to the reaction with bean proteins during fermentation.

Koji in Soy Sauce Production

Originally made in China from the first century incorporated fish pasted giving it a more pungent aroma. Soy was produced as a result of the fermenting process and was far thinner and liquid than what we now know as the paste like version of miso which was developed in the twelfth century in Japan. The role of koji in the production of miso is incredibly important as the variety used will vastly impact the resulting miso. Kome miso, made of rice and making up more than eighty percent of all miso, mugi miso, made of barley and mame miso where the koji-kin is cultered on soy bean provided an entirely soy based product. Of late people in North America and Europe are slightly adverse to consuming to much soy products as there is evidence they contain trypsin inhibitors, soyatoxin and phytoestrogens. So there is a move toward experimentation with other legumes including black bean, aduki and garbanzo. However miso production may vary in the future, one thing is for certain, koji will always play the foundational role.

Soy sauce has been indispensible in foods worldwide for decades with the Japanese variety particularly well regarded. Here koji is brewed with soy beans and roasted wheat and can be done cheaply and easily or crafted into the premium, complex soy sauce found in high-end sushi restaurants. Many people have been incorporating it seamlessly into western dishes. There are little to no health benefits to soy sauce, other than than which comes from the enzymes brought on during fermentation that aid digestion.

Tamari, which contains a byproduct of miso that can be substituted for the wheat used in soy sauce, making it gluten-free.

Koji in Rice Vinegar Production

In rice vinegar, koji ride and untreated rice are treated with additional bacteria to produce acid resulting in vinegar. Japanese rice vinegar is generally clear or very light yellow in colour and very mild in flavour and acidity. Rich in amino acids it aids in promoting a strong immune system by battling free radicals in the body. It is also is extremely beneficial in the absorption of vitamin C, helps to ease stress and breaks down and flushes out lactic acid buildup which can lead to muscle and joint aches and cramps.

Shio koji is now very popular. It is a mix of three parts koji to one part salt. It takes about seven to ten days to produce a condiment with a sweet and salty aroma. Shio koji can be used as a healthy replacement for salt in almost any dish or sauce as it contains less than half of the sodium content per volume, while at the same time providing a far richer taste than salt alone. It acts as an ideal tenderizing agent, is rich in fiber and vitamins and helps in digestion, anti-aging and clearer skin.

While there are certain health benefits to koji, it’s primary role is in the preservation of food and condiments and it the key element to boosting the taste in foods popular throughout the world. There is no need to limit koji to strictly specifically Japanese cuisine or more generally traditional Asian dishes. I will help inject the depth of flavour known as ‘umami’ or ‘taste number five’ that is trending in all international cooking these days. Get creative in finding new ways to introduce the unique properties of koji into your daily meals.