Mastering Shoyu making from a pro brewer at Daitoku Shoyu (vol.2)

Daitoku Shoyu has been making their Shoyu in a traditional natural brewing method in Yabu city, a beautiful mountainous district in Northern part of Hyogo prefecture.

The third and fourth generation Kozo and Takushi Jokei taught us how to make Shoyu from scratch. This report is the second part of the intensive Shoyu making camp at an old folk house which was once owned by a silkworm breeder in Yabu.

In the previous report vol.1, we visited Daitoku Shoyu’s brew factory and learned the basic of Shoyu making. In this volume, we move to the venue where we practice Koji and Shoyu making, and experience 3 days process in one day.

↓ Read the previous report vol.1 ↓

Mastering Shoyu making from a pro brewer at Daitoku Shoyu (vol.1)

✔日本語記事(Japanese article)

大徳醤油さんに教わる醤油づくりA to Z 醤油じかん上級編(後編)

Our venue for Shoyu Koji camp Oya Osugi

Oya Osugi, a 180 years old folk house that used to breed silkworms.

Cool sign board made by CHOAK BOY for this event.

Farming village Yabu values their rural culture

To our happy surprise, Takushi Jokei arranged a venue that we cannot expect any better. The place is called Oya Osugi (pronounced as “Ohya Ohsugi”), a 180 years old folk house that used to be owned by a silkworm breeder. Now it’s renovated as an event space and an accommodation.

Sericulture had been thriving business in Yabu for a long time, so there are still many three-story houses like this in the city. The industry itself fell into a decline, but local people values their folk culture, including an old festival and dance called “Osugi Zanzako Odori” that is registered as one of the selected intangible folk-cultural properties in Osugi area.

Interior of Oya Osugi.

When you enter Oya Osugi, you will see immediately that it’s a two-story ceiling. The house used to be three-story, but they removed the second floor to renovate it to an accommodation. The house is now managed by Mr. Kawabe, who normally works as a florist at Kimamori, located at a foot of Takeda castle. He has been looking after Oya Osugi for three years since the renovation, and he just turned up for our event as a local messenger to explain the background of this place.

Oya Osugi is fully supported by local people

Mr. Kawabe: “In Oya district, we have about 14 houses like this but only 7 of them are used. Most of the old folk houses have no visitors except for the new yeas days and summer and have been just about maintained by local people. Oya Osugi has just entered its third year, and much is repaired with a great local support. Everyone has a job and I am a florist too. So we work in shift to maintain this kind of house although none of us is specialized in hotel service. Oya Osugi was registered as one of the selected intangible folk-cultural properties, so it’s not allowed to break it down or renovate anymore.”

Participant: “I hear that this house used to breed silkworms upstairs?”

Mr. Kawabe: “That’s right. They used to grow silkworms on the second and the third floors. They made fire on this first floor and used the chimney for air condition. If you take a close look at the wall and pillars, you will notice that they are a bit black. Now the house functions as an accommodation, and according to the law we had to renovate it into a two-story house.”

Participant :“Did they used to sell textile here too?”

Mr. Kawabe : “No, only the materials were sold to neighbouring cities like Kyoto.”

Upstairs on the second floor (which used to be the third floor), there are guest rooms. It’s fully equipped with comfortable beds, clean linen, toilet and a small table. They do look professional hotel rooms.

Guest room at Oya Osugi.

Long waited lunch time

Our lunch was prepared by Tomoya Nishio. He is a travelling chef, and now temporarily settled in Oya to become an apprentice with a local mountain vegetable hunter.

Tomoya Nishio explaining about lunch menu.

Salad: flying squid from Hamasaka flavoured with freshly squeezed Shoyu. Optionally with Saishikomi-Shoyu from Daitoku Shoyu.

Curry with watercress sauce. Watercress grows in clusters in Tajima area. It was so good that some got even second serving.

Nougat glacé for dessert.

Full stomach, ready to make Koji!

After lunch, we finally started making Koji for Shoyu.

Tools to make Koji.

Steaming the soaked soybeans

Soybeans soaked overnight.

Takushi washed and soaked soybeans the day before. We are going to steam this in a special cooker specially made for soybeans.

A soybean steamer.

Roast wheat

In the meantime, wheat needs to be roasted until golden brown on a flying pan. Important to make sure not to make it burned.

Left: raw wheat. Right: roasted wheat. You can see that it’s a bit bigger.

Crush the roasted wheat

After the wheat is roasted, ground it coarsely in a blender.

Grounded wheat.

Soybeans are now steamed

It’s efficient to steam the soybeans and roast the wheat at the same time because both are time consuming.

This time, soybeans were cooked in a pressure pan. It took about 8 minutes to reach the highest pressure, then we cooked the beans for 15 minutes. Finally we put off the fire and left the pan for 15 minutes on after heat.

Steamed soybeans.

Soft enough to squash with fingers.

Cool down the cooked soybeans and wheat to mix

When the beans and the wheat are cool enough to touch, mix them together with hands.

Mixing the beans and the wheat.

Inoculate Koji starter

Finally Koji starter is sprinkled on the mixture.

Sprinkling the starter spore evenly.

After that, mix them with hands to inoculate the spore on entire mixture.

Mixing them further to spread the starter.

This time, we decided to leave the mixture at room temperature and wait until it starts to produce more heat in the next 17 hours.

Normally the whole Koji making takes at least three days, but specially for this event, Takushi prepared Koji at 20 hours and 36 hours in advance to show us how mycelia start to spread. When we inserted our hands in the mixture, we could feel a mild heat produced by Aspergillus Oryzae.

Warm Koji.

This is Koji that’s completed at 48 hours. The green fungal spore is visible.

Shoyu industry now

Daitoku Shoyu was named after Mt. Daitoku in Yabu city. The current province of Tajima includes Yabu, Toyooka, Asago city, Kami and Shinonsen cho towns. A lot of Ayu, or sweetfish live in the clear stream of Oya river. Daitoku Shoyu uses the subsoil water for their Shoyu making too.

Declining Shoyu production in Japan. Why not revalue Shoyu made by hands?

Now it’s time for Takushi’s lecture on Shoyu industry.

The production of Shoyu has been declining since 1970s. About one million two hundred thousand kilo litres has been used in Japan, and it was said that the industry falls into crisis when the usage hits below one million hundred kilo litres. Nevertheless it is already eight hundred thousand kilo litres. The average consumption per person in a year is 1.9 litres. The price of Shoyu has been falling too.

“Only about 2 litres in a year. Do you realize that this is very little? Still, the market price of Shoyu is collapsed. This makes me wonder and think that it’s better to spend for a good quality Shoyu, particularly if you use only 1.9 litres in a year.”, Takushi said.

30 to 40 Shoyu breweries are closed every year

There used to be around ten thousand local Shoyu breweries in Japan but now only around 1200. Every town used to have their own local Shoyu brewery that deliver the Shoyu to each home. Such tradition has faded away since the big market revolution and people can buy cheap Shoyu at a big chain supermarket.

Currently a half of national market is covered by 5 majour Shoyu companies, and the next 25% by 15 to 20 semi-majour companies. At last, the rest by the 1200 local small Shoyu breweries.

A big mission of small local breweries: carrying on the traditional Shoyu making

“This means that Shoyu demands in Japan can be filled by those majour companies, but small breweries have a very important mission to keep the traditional Shoyu making for future. Most of those 1200 local breweries are around 100 years old but they don’t have successors. Obviously after 100 years the facility is getting very old too, but they simply cannot invest on it anymore. So a new entry is nearly impossible in this industry. A fast brewing method has been standardized at big companies where they add yeast or extra heat retention, which is cost saving. This resulted in a difficult situation for small breweries that value their traditional brewing where we let natural climate change in four seasons and let nature do their jobs. And I want to change that. This is my biggest fuel to call the society to reevaluate the traditional Shoyu making.”, says Takushi.

Takushi Jokei, explaining about the current situation of Shoyu industry in Japan

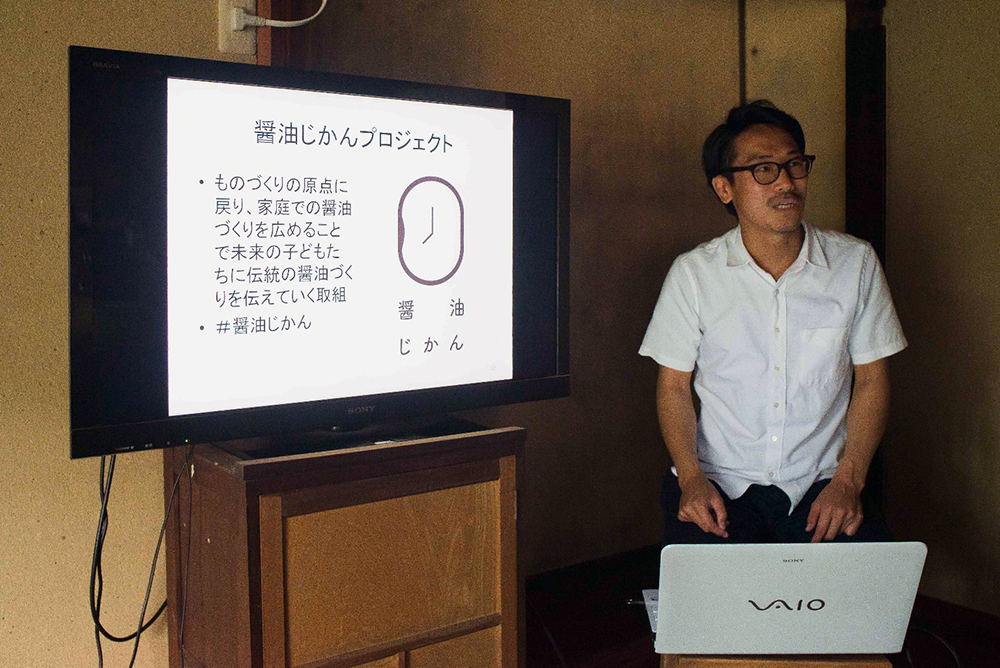

Shoyu Jikan (Shoyu time) project

Takushi realized “Shoyu Jikan (Shoyu time) project” by crowdfunding last year. The aim of this project is to reach public by spreading home Shoyu making to increase the awareness of the traditional Shoyu making. The official website has launched in February this year, and anyone can be a part of home Shoyu brewers.

Registration to Shoyu Jikan partner and host a workshop

If you register yourself up to this “Shoyu Jikan Partner”, you can host a home Shoyu making workshop anytime and anywhere you want.

This aim is to increase the people who can teach the traditional way of Shoyu making and bring the custom back to each home.

“I hope that anyone, even those who never had interest in Shoyu before can experience one year of Shoyu making at home and understand what it takes to make it. If you can be a part of this tradition, local culture will be protected. Everything should start from a kitchen at home. I would be happy if more people join this project to become a member.”

Takushi talking about Shoyu Jikan project.

Now we begin with our Shoyu making

After the lecture, it was time to prepare Shoyu from the Koji from Daitoku Shoyu. We need salt, water and a big glass container.

Making brine and add Koji

First, we dissolve the distributed salt in water using a bowl and a spatula.

Then pour the brine into a glass container and add Koji all at once. Everyone is excited with spores kicked up from the jar.

Mixing Koji in brine

When all Koji went in the jar, mix them very well with a spatula. That’s it for a day 1!

Koji in brine.

The mixture needs to be stirred every day for about a week, then less time after that. It’s fine if you forget some days, but when a climate gets too hot, you will see film yeast growing on the surface. That would be a sign that your mixture needs some air, so you can stir it more often in summer.

Do not mix to much! Break down the protein by enzyme and not your spatula

Shoyu makers all say that “Do not mash the beans, let Koji do it.” As it suggests, a fermentation will be disturbed if beans are smashed with Kai sticks. We should not mix it too much so the enzyme from Koji can break the protein down.

“It’s advisable to keep the jar at a place where you see often. Treat it like your pet, but don’t spoil it. Literally.”

For a year from now, your life with Shoyu Moromi mash starts. You can also share the progress on Instagram under hashtag key “#醤油じかん”. The community of home Shoyu maker is gradually growing.

Filtering well brewed Shoyu Moromi

The event continues. To our surprise, Takushi had ordered a mini home size Shoyu filter press with help of local carpenter.

Home size Shoyu filter press with help of local carpenter.

Next to it, there are well brewed whole soybeans Shoyu and Saishikomi Shoyu to be pressed. Takushi wanted us to experience the last part of Shoyu making too.

Moromi mash was poured into these filter press, and we let liquid to come out naturally first. Later, we added a little pressure to squeeze the rest.

Filtering Shoyu Moromi with home size filter press.

Freshly squeezed Shoyu!

We sample tasted the freshly squeeze Shoyu. Applause from everywhere. I don’t know how to put in words. In this event we didn’t only experience 3 days Koji making, but also one-year process of Shoyu making – well, at least a glimpse of it.

Dinner by Tomoya Nishio chef

People were already in heaven after the unforgettable experience, but that was not the end. Tomoya Nishio made dinner with using a blessing from nature in Tajima.

Sashimi of Japanese amberjack from Hamasaka and yellowtail, served with Allium gray and Shoyu Moromi.

Warm salad of fresh vegetable from Aichi.

A mountain salad of wild watercress.

Spaghetti of firefly squid from Hamasaka.

Cheese cake for dessert.

On the top of that, Takushi’s childhood friend Kazuhiro showed up to bring a bottle of Junmai Ginjo to warm up the dinner. He runs an organic Sake shop in Yabu, and quickly came by to say “hi” (ending up staying much longer than he expected..)

The atmosphere was relaxed, intimate and overall very happy.

“Tajima Homare” Junmai Ginjo from Yamadaya Shoten.

It’s not done yet. Looking after Koji overnight

After the dinner, we enjoyed chatting, taking a bath, and sometimes checking up on Koji’s temperature. Koji making is already a part of our life!

Next morning we could see the Koji is getting a fluffier and mycelia started to grow.

Koji at around 18 hours.

To finish, Tomoya made a beautiful quiche plate for our breakfast.

It was a very intensive camp with so much to learn and experience. Way more than what you could expect from two days camp.

The culture is made and carried on by people, and it starts from home and bond with neighbors and a local community. That is what we remembered in those two days. I’m very happy that I hosted this event and everyone who came with me to Yabu to share the moment.

To end this report, I’d like to express my special thanks to Daitoku Shoyu for everything that they organized, Mr. Kawabe for arranging Oya Osugi, Tomoya Nishio for cooking great food, and everyone else who was involved in this project. Thank you very much for all attendee who became a part of Shoyu Jikan project too.

Front from right: Takushi Jokei and his father Kozo Jokei

↓ Read the previous report vol.1 ↓

Mastering Shoyu making from a pro brewer at Daitoku Shoyu (vol.1)

✔日本語記事(Japanese article)

大徳醤油さんに教わる醤油づくりA to Z 醤油じかん上級編(後編)

Support

Daitoku Shoyu

Daitoku Shoyu online shop

Daitoku Shoyu Facebook page

Daitoku Shoyu Instagram

Oya Osugi

Related links

A travelling chef Tomoya Nishio

Yamadaya Shoten: Address: Junisho 981−2, Yabu, Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan, 〒667-0102 / Phone: +81 79-664-0008

CHOAK BOY