小計: ¥500

Homebrew enthusiasts gather to the exclusive talks by fermentation masters of Koji, Miso and microbes in life – Hacco festival in Osaka

Ever dreamed of meeting experts in traditional fermentation in Japan? Here’s what you missed.

4th of May had been pinned on my agenda for nearly four months since Nakaji san said that there’s going to be a Hacco festival in Osaka.

I was supposed to leave Japan on the very day, but the notice made me extend my stay as I knew that the festival was going to be a sort of “power spot” – as we like to call it – where a great deal of energy will meet.

The host Nakaji san, Minami Nakaji Tomoyuki is a Koji and fermentation culture researcher, a meditator, a therapist, a great cook and also a former Sake brewer in Terada Honke Natural Sake brewery. He travels light and freely to teach people how to make Koji, how fermentation in life can affect one’s health, as well as guiding people how to relax the body and mind so one can live stress-free life.

This time he invited four special guests with different backgrounds. What they have in common is Koji (and fermentation), which is the main theme of this Hacco festival. People were expected to meet their fellow “fermenters”, share the moment and find hints and tips to further “brew” their life styles.

In the morning of the event, I saw nearly 100 excited people gathering around the elegant Neo-Renaissance architecture in Nakanoshima. The venue was Osaka Central Public Hall, a beautiful red-brick building established in 1918, that is a symbol to Osaka people today.

Not to mention the seminar room had refined decor and historic atmosphere, the mood in the crowd was very positive, happy and affectionate. Everyone seemed to be sharing some sort of secret together, giggling and smiling, waiting for exclusive talks to be done by those special guests.

Koji – what’s behind everything you need for Washoku. The head of 360 years old Tane Koji maker Hishiroku talks

The first presenter was Akihiko Sukeno, the head of Hishiroku Moyashi, a 360 years old seed Koji maker in Kyoto. Despite of his achievement and career, Akihiko is such a friendly man with humor. His first question to the audience was “Did anybody get lost on the way to here today? – Good, it wasn’t only me.”

He began his presentation with briefly sharing the origin and history of Koji.

Kyoto was once a capital where more than 300 Sake breweries (including small family business) concentrated to fulfill the demands.

In those days, they had no advanced facilities to make and store Koji so the quality was presumably very bad. So Sake brewers started making Koji on their own, resulting a serious financial problem to Moyashiya, the seed Koji makers.

At the end of Heian period, the feudal government established Koji-za to regulate illegal Sake making and to secure the revenue generated by the tax on alcohol. Only the officially approved could make and sell Koji. Kitano Koji-za in Kyoto Kitano Tenmangu is the famous one. The situation lasted until the mid 1400s until Bunan Koji riot caused the corruption of Koji-za. Only some survived and sustained seed Koji making until today.

Akihiko humbly says, “In fact my personal Koji career is only about 17 years.”

17 years ago, Sake wasn’t very popular compared to beer and wines in Japan. Since Moyashiya runs mostly on Sake industry, the situation wasn’t favorable but he started off his business anyway before a huge trend on Amazake, Shio-Koji, and any other condiment made of Koji hit the country. To his eyes, it’s quite amazing how the nation is crazy about Koji these days.

After going through the making of Sake, Miso and Shoyu, he finally went on to his expertise: Koji-kin.

It’s acknowledged as Japan’s national fungus in 2006, and the variety includes Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus sojae, and Aspergillus luchuensis. Aspergillus niger is a different type of Awamori fungus, thus not included in Koji-kin.

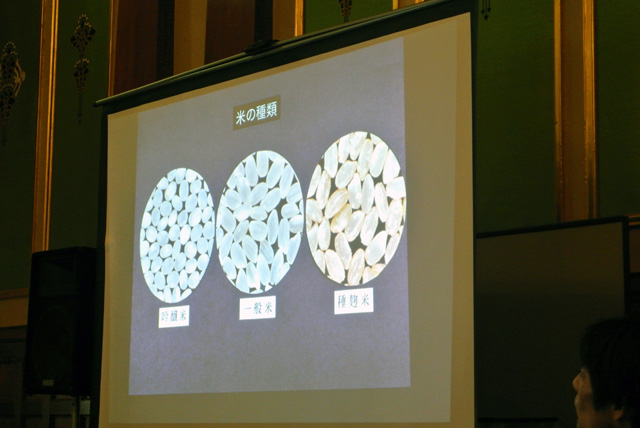

One of the difference between Koji and Tane/seed Koji making is rice polishing ratio. Tane Koji uses 3% polished brown rice (called Kohaku-mai), which is polished much less than the rice for Sake making. In this way, spores can have more surface area to grow and the necessary components for spore formulation such as phosphorus and potassium can be remained.

The technique to make Tane Koji is not much different from how it’s described in the old document made by Akaban, a competitor of Hishiroku about 360 years ago. This document also mentions (negatively) about Hishiroku and the other competitor Kuroban, that indicates Hishiroku’s presence at that time. The real establishment of the business is yet unknown.

The production of Tane Koji done at Hishiroku is very efficient. They sift sporulated rice to collect spores, and the remained rice grain would be finely milled. Both would be mixed to add some weight on spores so that they would fall onto the target. For home use this product is handy as we don’t have a professional facility to dust rice with spores. It’s also good for production wise at Hishiroku because there is really nothing to waste.

He also showed us that Koji-kin’s spore measures about 4-8μ big (or small..) and its mycelium is dia. 8-13μ and 1,000μ in length, whereas influenza virus is about 0.02-0.1μ.

In the picture below you will see that a small ball like thing which is Koji spore and the thick long thing which is mycelium.

Another difference in Tane Koji making is the usage of wood ashes in order to lower the pH level so the other bacteria cannot survive. Particularly Camellia trees are considered to be the best to transfer phosphorus and potassium to the rice, and also to make the spore long living.

With today’s advanced technology we can study the details of bacteria, but in earlier times people could only rely on its smell or visual look so there must have been 5 or 6 types of different bacteria mixed up in Tane Koji they were making, according to Akihiko. “Their standards very much depended on the colour of Moyashi and the clients’ feedback.”

The last thing he explained, which hit me the most, was the storage of the strains.

“For every strain we use more than one storage method at Hishiroku. We also choose several different locations to have them sheltered. This step is crucial, as all the fermented food would perish if these strains died. They need to be guarded even if it costs me my life.”

The whole time he was making jokes during presentation, but this last line showed his earnest attitude towards Tane Koji making, which supports Japan’s food culture without exaggeration.

Let’s dance on Koji song. The world’s first Hacco designer invites you to see the world of microbes

The next presenter is Hiraku Ogura, the one and only Hacco designer in the world. His official aim is to visualize the invisible activities by microbes though design works such as music animation about Koji, Miso and fermentation culture in Japan. He has also hosted a number of Koji workshops throughout the country, making the act more attainable.

Predictably, he played “Koji no uta” (A song of Koji) on screen to begin with. The animated intro broke the silence in the lecture room, and yet he wouldn’t stop challenging the audience.

“Let’s get up and dance on this song.” said Hiraku, not afraid of anything.

People are requested to copy his gesture, followed by the lyric in the song: “Umami masu, Amami masu”.

This very short line explains the whole process of enzymes in Koji breaking down protein into amino acid (Umami) and starch into sugar (Amami) in summary. The next dance movement making a gesture of wearing glasses with your hands, is of course indicating a microscope looking into the invisible microbes or Koji-kin, while we make clockwise turn expressing a journey to find them.

After a couple of times of rehearsal, he invited us all to dance on the actual music but it was so speedy to match the movement that immediately the group erupted into gales of laughter.

Beyond doubt the workout certainly made us all united. Relieved and finally seated, we all gazed at him, panting and wondering what his next proposition would be.

He explained to us that this activity was one of his approach as a Hacco desiner to introduce Koji making into public.

“Hacco designer” – this unusual title was initially proposd by one of press people who was interviewing him about his animation. Since he was in a transition stage from a designer in a classic sense to the one who specialized fermentation at that time, he adopted this title to identify himself.

His original background was cultural anthropology. After a strange turn of events, he moved to Europe to practice painting and went backpacking where he also learned human culture and practices through his own experiences.

Back in Japan and having missed a timing for a job search, he opened a guest house to further on enjoy his personal research on the field. Unfortunately, this decision later made him realize the lack of interaction with society, and with much consideration he started working as an in-house designer at a cosmetic company. Delighted, being busy and successful, he lived a lifestyle of excess until he got very sick from neglecting his health.

This was the turning point that he altered his career.

One day his worried friend took him to Takeo Koizumi, a former professor at Tokyo University of Agriculture.

At a glance the professor yelled at him: “You should eat Natto and Tsukemono, and drink Miso soup!”

Hiraku immediately followed this advice, that miraculously improved his poor health conditions. This made him finally understand the importance of the activities of microbes, and he decided to pursue his new interest in a laboratory at this university that Takeo taught.

By a quirk of fate he eventually left the company to work independent as Hacco designer. His mission included design works to revitalize the countryside area by helping local breweries to develop their product lines and to host events and workshops. He realized that the basis of the local culture was always derived from those local fermentation industry.

“The difference in food culture very much come from the difference in microbes.”, says Hiraku.

For example, rice Koji is traditionally used in Japan because Japanese mold (Aspergillus oryzae) grows a lot of spores whereas in China people make Koji from Mochi cake, a bigger culture media more suitable for mycelium to spread. Inevitably, this brought a difference in a sense of taste in their food culture as well.

Rhizopus, the common mold in Chinese Koji, produces mainly acid taste which fits for Shaoxing wine making for example. This wine usually is sit for fermentation for at least 5 years in order to make the initial sour and bitter taste milder. The longer it’s fermented, the richer and deeper the taste gets. Thanks to the high acid level, this Koji wouldn’t go off quickly and is therefore easy to store for a long time.

On the other hand, Aspergillus oryzae produces more enzyme to create sweet flavour. This is good for Sake making, though it also allows the other bacteria to jump in due to the lower acid level compared to rhizopus.

This character brought a need of Koji Muro (Koji room) as the making process required more delicate and protected environment to achieve the fresh and sensitive flavour in Sake.

This tells us that Japanese fermented food is supposed to last for a shorter period of time while Chinese one considers decades, sometimes a hundred years for fermentation in general. It’s a big proof that the characters of Koji defines the style of the food culture in the world.

To conclude, Hiraku said: “Hacco to me, is to discover the relationship between invisible nature and oneself.”

Only 2% of production output. The reason why he still sticks to the traditional brewing. The head of 300 years old Miso and Tamari maker talks about his faith

The third presenter was Takeshi Motoji, the owner of Tokai Jozo brewery in Suzuka city, Mie. The brewery has a history of 300 years establishment.

Together with 7 other fellow workers he continues to follow the traditional form of Tamari and Miso making from Edo period, utilizing the geographical character and the climate that’s suitable for natural brewing.

While the industry has been leaning towards automatic brewing with the advances in technology, Takeshi sticks to the manual process that requires a lot of hand work in order to deliver the original flavour to the exclusive clients.

The only ingredients are soybean and salt. The temperature in Kura (the storehouse) is uncontrolled, and he let microbes living in wooden barrels to do their jobs so soybeans would be naturally fermented. As might be expected, the production output is extremely low because of the long processing time, but he finds the huge potential and the necessity to keep this heritage.

He explained three ways to define the type of Miso: colour, taste and the ingredients.

The colour names the Miso white or red/brown, and the taste classifies it salty or sweet. The ingredients refers to the type of Koji used: rice Koji for Koji Miso, barley Koji for barley Miso and soybean Koji for Mame Miso.

Akadashi Miso is not something that includes Dashi even though the name suggests the idea.

It’s a blended Miso of Mame Miso and Shinshu Miso, creating a special brown colour and flavour. This is one of Chogo-Miso, the blended Miso that’s registered in Japan Agricultural Standards.

In Kyoto you will sometimes find what’s called Sakura Miso, which is also the same kind. To make this, Koji Miso is blended into Mame Miso in order to make the taste much milder.

Tokai Jozo used to deliver their Miso to a diner in Suzuka circuit, however, people didn’t like the Miso soup made out of it because of the unusual black colour compared to Miso soup that they were familier with. Those people’s Miso culture was, interestingly, based on Kansai area where they enjoy rather mild Miso soup. For that reason Takeshi customized the Miso by blending the traditional Mame Miso with Shinshu Miso so it would meet their desired taste.

Tokai Jozo’s Mame Miso, is made in Hatcho style although they cannot use the word “Hatcho” for branding.

It’s reserved for only two Miso factories: Maruya Hatcho Miso and Kakukyu Miso in Japan as it refers to the fact that the Miso factory is located approximately 870m west of Okazaki castle. The word “ha” means 8, and “cho” means one city block, so “Hatcho” counted 8 blocks in those days. Just to avoid confusion, Hatcho Miso and Mame Miso are still the same thing, said Takeshi.

Normally Mame Miso is made of soybean Koji and salt, fermented for 2 years. At Tokai Jozo this takes 3 years instead of 2. What is special about this Miso is that the water and sugar content is quite low so the end result has rather hard texture and a very dark colour due to the long fermentation time. It’s only produced in three prefectures in Japan: Aichi, Mie and Gifu.

If you are a food lover, you may have heard about Nagoya cuisine. Take Udon for example, there are three different types in Tokai area, depending on what Miso or Shoyu is used. Mame Miso for Miso nikomi Udon, Tamari in Ise Udon, and Shiro (white) Tamari for Kishimen noodle.

In old times, Miso was mainly traded by ships, which means that Miso factories were always located close to the harbor. Tokai Jozo used Shiroko harbor, but Interestingly they didn’t go out to the open sea. Instead, they sailed around Ise Bay and followed along Kiso three rivers (Kiso River, the Ibi River and the Nagara River). This way, they could realize the inland transportation without advanced vehicle that still didn’t exist.

One of the area that they delivered Tamari and Miso was Chiyo Bo Inari Shrine where they had some buffet style dining in Monzen-cho area, where they still keep a very long business relationship with Tokai Jozo today.

Takeshi also explained about Miso in general spontaneously.

As the name “Omiotsuke” suggests, Miso has been valued as a very important ingredient in Japanese kitchen. People already knew that it was vital to have Miso soup together with plenty of rice and vegetables to stay healthy from old times.

The nutritional value of soybean is already high, and the fermention gives an extra boost to it. The recent research also shows that peope who drink Miso soup can stay away from gastric ulcer.

The funny anecdote that he quickly shared was about the old manner to clean their tabacco pipes with a paper that’s dipped in Miso so the remainig fat and nicotine inside the pipe would be broken down. Takeshi thinks that this hints the way that the daily habit of having Miso soup can help cholesterol to be removed from blood veins.

“I believe it’s more effective if you have Miso soup everyday, instead of relying on nutritional supplement. If making Miso soup in the morning is difficult, you can also have it for your dinner.”, said Takeshi.

One of the last thing he mentioned, was about wooden barrels they use to make Miso. The fermentation works well thanks to this living microbes inside the barrels, which is a big reason why they keep the old barrels at the brewery.

The problem is that there are not a lot of successors in the industry in Japan, and they need to be very careful to maintain them. If the bamboo band gets loose, it would cause the leakage.

For that he introduced a program to grow young initiatives to learn how to make the wooden barrels, how to maintain them and so on.

“Let’s hope that we’ll get young hopes.”, said Takeshi.

“Keep good luck on your side. Enjoy your life. Don’t forget to thank. Keep giving. That will “ferment” your life in the end.” The radio personality talks about his and your dreams

The last presenter was Daisuke Sato, a radio personality of “Yume no Tane” together with his best friend Naoki Okada. Their missions are to encourage and support people’s dreams that eventually contribute to the society. You might still wonder why he was invited for this festival, but the way he communicates with people in Nakaji’s eyes is, in a way “fermented”.

There must be a connection between the microbe’s activities and human/social well-being, and in the same way that food gets more nutrition (and many other advantages) from fermentation, human must be able to benefit from it as well.

Daisuke is a great example of “the fermented man”, introduced Nakaji.

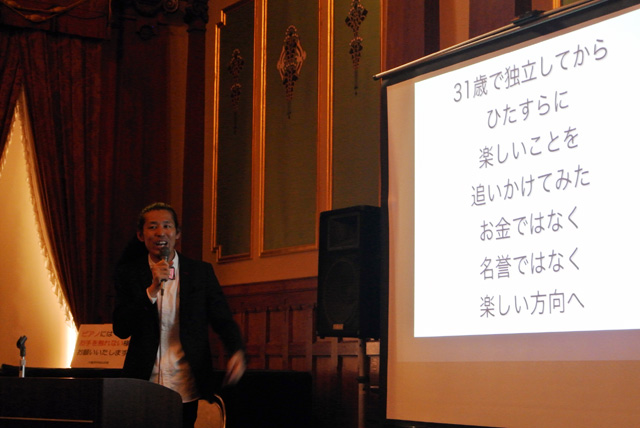

To begin with, Daisuke explained about his career. He used to be “a salaryman” until the age of 31, then he decided to work independently in order to pursue what really made him happy.

Together with Naoki he started an internet radio program that could be listened on smartphones. The idea to use the existing radio waves was progressive but also very unusual at that time. Nevertheless, his business was debt-free and grew six times bigger, acquiring 30,000 listeners. In June 2015, he launched a radio station called “Yume no Tane broadcast” and established 6 studios throughout the country, which now has 420 radio programs all together.

“One of the great things about this broadcast is that there are hardly any complaints on the programs. It’s only 0.1%.”, said Daisuke. The avarage amount of complaints in the media industry is 200 per program. This means that his programs are certainly making people happy.

His radio has been getting a lot attention on local media as well. Thanks to that, he is going to open a new studio in Okinawa in coming Autumn alonside of existing ones in Tokyo, Nagoya, Okayama, Hiroshima and Matsuyama.

Most of his programs do not have any financial sponsors. Without ads, every station broadcasts their programs at very small cost. This style enables the speakers to present their thoguhts and ideas without any interference, which Daisuke finds fantastic, as he sees that this attracts a lot of sympathy from the listeners and eventually the radio obtained 1.8 million access in number. Together with Naoki, he himself has a program called “LiFE” that they cast a spotlight on the individual dreams from listners.

The moment that triggered him to dive into the fermentation was in summer last year when he had a unusual high fever.

He never liked going to the hospital so he just did his routine activities but the fever didn’t go down even after a week. Naoki forced him to see a doctor and there they discovered his lungs inflammation.

Altough he still didn’t want to enter the hospital, he did reconsider about what he eats that might have been the cause of his sudden illness. Soon he remembered a cooking class in Osaka, and decided to take some of the lessons to learn various fermented food using Koji. The school is called “Okan no Koji”, run by Yoshimi Kobayashi, an expert in Koji making and home cooking. Through Yoshimi, he also got to know Nakaji who brought him to this Hacco festival.

During his presentation, he showed us uncountable number of pictures he took – music, nice cafes, beautiful architecture, some trips and friends. Clearly he enjoys his life fully, particularly through music, which is his other profession now.

“Think of children, they are full of life. I guess that’s because they are busy with expressing themselves all the time. At school they learn new things like painting, music, writing and so on… but when you grow up, suddenly those occasions are gone. You end up travelling between your work and home, and there isn’t enough time to do anything you like anymore.”

He continued, “What’s important is to keep your mind alive. When your mind gets warmed up, you are “fermented”. When it gets cold, it goes off. This change can happen in a blink, and can also influence what’s around you. Your daily attitude can maintain a good balance in your mind.”

What should we actually do? Daisuke told us to maintain a good condition. For example, to stay with someone you like and to do something you love. Trust your intuition, rather than focusing on efficiency or productivity. Keep giving. That would lighen up your environment.

The last tip he gave us was – “Do it now. Don’t give up and keep trying. Finish what you started. Most of all – don’t forget to thank.”

The whole room was filled with content atomosphere when all these talks were finished.

Everyone looked happy, inspired and loaded with high aspirations. The initial excited mood was certainly fermented after those five hours of continuous shared moments.

Personally I accomplished my aim on this day, which was simply to be there together with other microbes, and get infected with spirit of fermentation.

Review of the event

Hacco festival in Osaka

DATE:4th of May,2017 ※The event has ended.

TIME:11:00~16:00(open 10:30)

PLACE:OSAKA CITY CENTRAL PUBLIC HALL

【President of the event】

Nakaji(Minami Tomoyuki)

Koji and fermentation culture researcher, a meditator, a therapist, and President of Minami-ya.

・blog:http://ameblo.jp/motherwater-nakaji/

・Minami-ya:https://minamiyasun.jimdo.com/

【Guests】

Akihiko Sukeno, the head of Hishiroku Moyashi.

Hiraku Ogura, Hacco designer.

Takeshi Motoji, the owner of Tokai Jozo brewery.

Daisuke Sato, a radio personality of “Yume no Tane”.

【Event Details】

https://hakkoudaigaku.wixsite.com/fermentationfestival

【Next Event】

Hacco festival in Sapporo

石鎚黒茶・青(茶葉)

石鎚黒茶・青(茶葉)